Units and nonlinearity in Meep

From AbInitio

| Revision as of 03:19, 6 April 2006 (edit) Stevenj (Talk | contribs) ← Previous diff |

Revision as of 03:26, 6 April 2006 (edit) Stevenj (Talk | contribs) (→Using experimental Kerr coefficients) Next diff → |

||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

| The key to using correct magnitudes is nonlinear calculations in Meep is to realize that the units are still somewhat arbitrary: only the ''product'' <math>n_2 I</math> is significant, so as long as we get this product right we are fine. Moreover, we can choose our units of distance and our units of field strength independently and arbitrarily. So, if we are given <math>n_2</math> in some units like μm<sup>2</sup>/W we are free to use μm as our unit of distance and W as our units of power. | The key to using correct magnitudes is nonlinear calculations in Meep is to realize that the units are still somewhat arbitrary: only the ''product'' <math>n_2 I</math> is significant, so as long as we get this product right we are fine. Moreover, we can choose our units of distance and our units of field strength independently and arbitrarily. So, if we are given <math>n_2</math> in some units like μm<sup>2</sup>/W we are free to use μm as our unit of distance and W as our units of power. | ||

| - | For example, suppose now that we are given some experimental value of <math>n_2</math> in "real" units, say 3×10<sup>–8</sup>μm<sup>2</sup>/W (silica glass). Of course, this is very small (semiconductors can be much more nonlinear), so to compensate suppose let's plan to use an unrealistic 1 MW<sup>2</sup> of power in our structure (say a waveguide). To implement this in Meep, for convenience we'll use μm as our unit of distance and W as our units of power. First, we'll set <math>\chi^{(3)}</math> from <math>n_2</math> and ''n'' in these units: <math>\chi^{(3)} = 4n^2 (3\times 10^{-8})/3</math> where ''n'' is the linear index. Then we simply monitor the power going through our waveguide (or whatever) and change the current amplitude (note that power ~ ''J''<sup>2</sup>) until we get 10<sup>6</sup>. | + | For example, suppose now that we are given some experimental value of <math>n_2</math> in "real" units, say 3×10<sup>–8</sup>μm<sup>2</sup>/W (silica glass). Of course, this is very small (semiconductors can be much more nonlinear), so to compensate suppose let's plan to use an unrealistic 1 MW of power in our structure (say a waveguide). To implement this in Meep, for convenience we'll use μm as our unit of distance and W as our units of power. First, we'll set <math>\chi^{(3)}</math> from <math>n_2</math> and ''n'' in these units: <math>\chi^{(3)} = 4n^2 (3\times 10^{-8})/3</math> where ''n'' is the linear index. Then we simply monitor the power going through our waveguide (or whatever) and change the current amplitude (note that power ~ ''J''<sup>2</sup>) until we get 10<sup>6</sup>. |

| To monitor the power in a structure, we can use a variety of functions (see the [[Meep Reference]]). One can get the power flux directly through the <code>meep-fields-flux-in-box</code> function. Or, one can alternatively get the intensity at a single point by calling <code>get-field-point</code> and passing <code>Sx</code> etc. for the component. One thing to be cautious about is that these return the power or intensity at one instant in time, and not the time-average unless you use complex-valued fields (which are problematic for nonlinear systems). | To monitor the power in a structure, we can use a variety of functions (see the [[Meep Reference]]). One can get the power flux directly through the <code>meep-fields-flux-in-box</code> function. Or, one can alternatively get the intensity at a single point by calling <code>get-field-point</code> and passing <code>Sx</code> etc. for the component. One thing to be cautious about is that these return the power or intensity at one instant in time, and not the time-average unless you use complex-valued fields (which are problematic for nonlinear systems). | ||

Revision as of 03:26, 6 April 2006

| Meep |

| Download |

| Release notes |

| FAQ |

| Meep manual |

| Introduction |

| Installation |

| Tutorial |

| Reference |

| C++ Tutorial |

| C++ Reference |

| Acknowledgements |

| License and Copyright |

For linear calculations in electromagnetism, most quantities of interest are naturally expressed as dimensionless quantities, such as the ratio of the wavelength to a given lengthscale, the transmitted or reflected power as a fraction of input power, or the lifetime in units of the optical period. Matters are more complicated when one includes nonlinear effects, however, because in this case the absolute amplitude of the electric field becomes significant. On this page, we discuss how to relate Meep's units to those of experimental quantities relevant for nonlinear problems.

Kerr nonlinearities

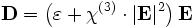

Meep supports instantaneous Kerr nonlinearities characterized by a susceptibility χ(3), corresponding to a constitutive relation (in Meep's units):

However, the number usually reported for the strength of the Kerr nonlinearity is the AC Kerr coefficient n2, defined by the effective change in refractive index Δn for a planewave with time-average intensity I travelling through a homogeneous Kerr material:

- Δn = n2I

(This equation itself is somewhat subtle: it is not the actual instantaneous change in refractive index at every point. Rather, it is a sort of average change in index, and in particular is the change in effective index βc / ω where β is the propagation constant.)

The relationship between n2 and χ(3), in Meep's units, is:

where n is the linear refractive index  .

.

Using experimental Kerr coefficients

The key to using correct magnitudes is nonlinear calculations in Meep is to realize that the units are still somewhat arbitrary: only the product n2I is significant, so as long as we get this product right we are fine. Moreover, we can choose our units of distance and our units of field strength independently and arbitrarily. So, if we are given n2 in some units like μm2/W we are free to use μm as our unit of distance and W as our units of power.

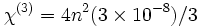

For example, suppose now that we are given some experimental value of n2 in "real" units, say 3×10–8μm2/W (silica glass). Of course, this is very small (semiconductors can be much more nonlinear), so to compensate suppose let's plan to use an unrealistic 1 MW of power in our structure (say a waveguide). To implement this in Meep, for convenience we'll use μm as our unit of distance and W as our units of power. First, we'll set χ(3) from n2 and n in these units:  where n is the linear index. Then we simply monitor the power going through our waveguide (or whatever) and change the current amplitude (note that power ~ J2) until we get 106.

where n is the linear index. Then we simply monitor the power going through our waveguide (or whatever) and change the current amplitude (note that power ~ J2) until we get 106.

To monitor the power in a structure, we can use a variety of functions (see the Meep Reference). One can get the power flux directly through the meep-fields-flux-in-box function. Or, one can alternatively get the intensity at a single point by calling get-field-point and passing Sx etc. for the component. One thing to be cautious about is that these return the power or intensity at one instant in time, and not the time-average unless you use complex-valued fields (which are problematic for nonlinear systems).

You may have been hoping for a simple formula: set the current to x to get y power. However, this is not feasible since the amount of power or field intensity you get from a current source depends on the source geometry, the dielectric structure, and so on. (And a formula for the units of current is not terribly useful because usually the current source in an FDTD calculation is artifically inserted to create the field, and doesn't correspond to the current source in a physical experiment.)