Meep Reference

From AbInitio

(diff) ←Older revision | Current revision | Newer revision→ (diff)

| Meep |

| Download |

| Release notes |

| FAQ |

| Meep manual |

| Introduction |

| Installation |

| Tutorial |

| Reference |

| C++ Tutorial |

| C++ Reference |

| Acknowledgements |

| License and Copyright |

Here, we document the features exposed to the user by the Meep package. We do not document the Scheme language or the functions provided by libctl (see also the libctl User Reference section of the libctl manual).

This page is simply a compact listing of the functions exposed by the interface; for a gentler introduction, see the Meep tutorial. Also, we note that this page is not, and probably never will be, a complete listing of all functions. In particular, because of the SWIG wrappers, every function in the C++ interface is accessible from Scheme, but not all of these functions are documented or intended for end users.

See also our parallel Meep instructions for parallel (MPI) machines.

Contents |

Input Variables

These are global variables that you can set to control various parameters of the Meep computation. In brackets after each variable is the type of value that it should hold. (The classes, complex datatypes like geometric-object, are described in a later subsection. The basic datatypes, like integer, boolean, cnumber, and vector3, are defined by libctl.)

-

geometry[list ofgeometric-objectclass] - Specifies the geometric objects making up the structure being simulated. When objects overlap, later objects in the list take precedence. Defaults to no objects (empty list).

-

sources[list ofsourceclass] - Specifies the current sources to be present in the simulation; defaults to none.

-

symmetries[list ofsymmetryclass] - Specifies the spatial (mirror/rotation) symmetries to exploit in the simulation (defaults to none). The symmetries must be obeyed by both the structure and by the sources. See also: Exploiting symmetry in Meep.

-

pml-layers[list ofpmlclass] - Specifies the absorbing PML boundary layers to use; defaults to none.

-

default-material[material-typeclass] - Holds the default material that is used for points not in any object of the geometry list. Defaults to

air(ε of 1). -

geometry-lattice[latticeclass] - Specifies the size of the unit cell (which is centered on the origin of the coordinate system). Any sizes of

no-sizeimply (effectively) a reduced-dimensionality calculation (but a 2d xy calculation is especially optimized); seedimensionsbelow. Defaults to a cubic cell of unit size. -

dimensions[integer] - Explicitly specifies the dimensionality of the simulation, if the value is less than 3. If the value is 3 (the default), then the dimensions are automatically reduced to 2 if possible when

geometry-latticesize in the z direction isno-size. Ifdimensionsis the special value ofCYLINDRICAL, then cylindrical coordinates are used and the x and z dimensions are interpreted as r and z, respectively. Ifdimensionsis 1, then the cell must be along the z direction and only Ex and Hy field components are permitted. Ifdimensionsis 2, then the cell must be in the xy plane. -

m[number] - For

CYLINDRICALsimulations, specifies that the angular φ dependence of the fields is of the form eimφ (default ism=0). If the simulation cell includes the origin r = 0, thenmmust be an integer. -

accurate-fields-near-cylorigin?[boolean] - For

CYLINDRICALsimulations with |m| > 1, compute more accurate fields near the origin r = 0 at the expense of requiring a smaller Courant factor. Empirically, when this option is set totrue, a Courant factor of roughly min[0.5,1 / ( | m | + 0.5)] (or smaller) seems to be needed. The default isfalse, in which case the Dr, Dz, and Br fields within |m| pixels of the origin are forced to zero, which usually ensures stability with the default Courant factor of 0.5, at the expense of slowing convergence of the fields near r = 0. -

resolution[number] - Specifies the computational grid resolution, in pixels per distance unit. Defaults to

10. -

k-point[falseorvector3] - If

false(the default), then the boundaries are perfect metallic (zero electric field). If a vector, then the boundaries are Bloch-periodic: the fields at one side are times the fields at the other side, separated by the lattice vector

times the fields at the other side, separated by the lattice vector  . The

. The k-pointvector is specified in Cartesian coordinates, in units of 2π/distance. (This is different from MPB, equivalent to taking MPB'sk-pointsthrough the functionreciprocal->cartesian.) -

ensure-periodicity[boolean] - If

true(the default), and if the boundary conditions are periodic (k-pointis notfalse), then the geometric objects are automatically repeated periodically according to the lattice vectors (the size of the computational cell). -

eps-averaging?[boolean] - If

true(the default), then subpixel averaging is used when initializing the dielectric function (see the Farjadpour et al. reference in Citing Meep). The input variablessubpixel-maxeval(default100000) andsubpixel-tol(default1.0e-4) specify the maximum number of function evaluations and the integration tolerance for subpixel averaging. Increasing/decreasing these, respectively, will cause a more accurate (but slower) computation of the average ε (with diminishing returns for the actual FDTD error). -

force-complex-fields?[boolean] - By default, Meep runs its simulations with purely real fields whenever possible. It uses complex fields (which require twice the memory and computation) if the

k-pointis non-zero or ifmis non-zero. However, by settingforce-complex-fields?totrue, Meep will always use complex fields. See also: Complex fields in Meep. -

filename-prefix[string] - A string prepended to all output filenames. If

""(the default), then Meep uses the name of the current ctl file, with ".ctl" replaced by "-" (e.g.foo.ctluses a"foo-"prefix). See also Output file names. -

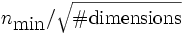

Courant[number] - Specify the Courant factor S which relates the time step size to the spatial discretization: cΔt = SΔx. Default is

0.5. For numerical stability, the Courant factor must be at most , where nmin is the minimum refractive index (usually 1), and in practice S should be slightly smaller.

, where nmin is the minimum refractive index (usually 1), and in practice S should be slightly smaller.

-

output-volume[meep::geometric_volume*] - Specifies the default region of space that is output by the HDF5 output functions (below); see also the

(volume ...)function to createmeep::geometric_volume*objects. The default is'()(null), which means that the whole computational cell is output. Normally, you should use the(in-volume ...)function to modify the output volume instead of settingoutput-volumedirectly. -

output-single-precision?[boolean] - Meep performs its computations in double precision, and by default its output HDF5 files are in the same format. However, by setting this variable to

true(default isfalse) you can instead output in single precision which saves a factor of two in space. -

progress-interval[number] - Time interval (seconds) after which Meep prints a progress message; default is 4 seconds.

-

extra-materials[list ofmaterial-typeclass] - By default, Meep turns off support for material dispersion, nonlinearities, and similar properties if none of the objects in the

geometryhave materials with these properties—since they are not needed, it is faster to omit their calculation. This doesn't work if you use amaterial-function, though (materials via a user-specified function of position, instead of just geometric objects). If only your material function returns a nonlinear material, for example, Meep won't notice this unless you tell it explicitly viaextra-materials.extra-materialsis a list of materials that Meep should look for in the computational cell, in addition to any materials that are specified by geometric objects. You should list any materials (other than scalar dielectrics) that are returned bymaterial-functions here.

The following require a bit more understanding of the inner workings of Meep to use (see also the SWIG wrappers).

-

structure[meep::structure*] - Pointer to the current structure being simulated; initialized by

(init-structure)which is called automatically by(init-fields)which is called automatically by any of the(run)functions. -

fields[meep::fields*] - Pointer to the current fields being simulated; initialized by

(init-fields)which is called automatically by any of the(run)functions. -

num-chunks[integer] - Minimum number of "chunks" (subarrays) to divide the structure/fields into (default 0); actual number is determined by number of processors, PML layers, etcetera. (Mainly useful for debugging.)

Predefined Variables

Variables predefined for your convenience and amusement.

-

air,vacuum[material-typeclass] - Two aliases for a predefined material type with a dielectric constant of 1.

-

perfect-electric-conductorormetal[material-typeclass] - A predefined material type corresponding to a perfect electric conductor (at the boundary of which the parallel electric field is zero), technically

.

.

-

perfect-magnetic-conductor[material-typeclass] - A predefined material type corresponding to a perfect magnetic conductor (at the boundary of which the parallel magnetic field is zero), technically

.

.

-

nothing[material-typeclass] - A material that, effectively, punches a hole through other objects to the background (

default-material). -

infinity[number] - A big number (1.0e20) to use for "infinite" dimensions of objects.

-

pi[number] - π (3.14159...).

Constants (enumerated types)

Several of the functions/classes in Meep ask you to specify e.g. a field component or a direction in the grid. These should be one of the following constants:

-

directionconstants - Specify a direction in the grid. One of

X,Y,Z,R,Pfor: x, y, z, r, φ, respectively. -

boundary-sideconstants - Specify particular boundary in some direction (e.g. + x or − x). One of

LoworHigh. -

componentconstants - Specify a particular field (or other) component. One of

Ex,Ey,Ez,Er,Ep,Hx,Hy,Hz,Hy,Hp,Hz,Bx,By,Bz,By,Bp,Bz,Dx,Dy,Dz,Dr,Dp,Dielectric,Permeability, for: Ex, Ey, Ez, Er, Eφ, Hx, Hy, Hz, Hr, Hφ, Bx, By, Bz, Br, Bφ, Dx, Dy, Dz, Dr, Dφ, , μ, respectively.

, μ, respectively.

-

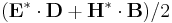

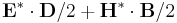

derived-componentconstants - These are additional components, which are not actually stored by Meep but are computed as needed, mainly for use in output functions. One of

Sx,Sy,Sz,Sr,Sp,EnergyDensity,D-EnergyDensity,H-EnergyDensityfor: Sx, Sy, Sz, Sr, Sφ (components of the Poynting vector ),

),  ,

,  ,

,  , respectively.

, respectively.

Classes

Classes are complex datatypes with various "properties" which may have default values. Classes can be "subclasses" of other classes; subclasses inherit all the properties of their superclass, and can be used any place the superclass is expected. An object of a class is constructed with:

(make class (prop1 val1) (prop2 val2) ...)

See also the libctl manual.

Meep defines several types of classes, the most numerous of which are the various geometric object classes (which are the same as those used in MPB. You can also get a list of the available classes, along with their property types and default values, at runtime with the (help) command.

lattice

The lattice class is normally used only for the geometry-lattice variable, which sets the size of the computational cell. In MPB, you can use this to specify a variety of affine lattice structures. In Meep, only rectangular Cartesian computational cells are supported, so the only property of lattice that you should normally use is its size.

-

lattice - Properties:

-

size[vector3] - The size of the computational cell. Defaults to unit lengths.

If any dimension has the special size no-size, then the dimensionality of the problem is (essentially) reduced by one; strictly speaking, the dielectric function is taken to be uniform along that dimension.

Because Maxwell's equations are scale-invariant, you can use any units of distance you want to specify the cell size: nanometers, inches, parsecs, whatever. However, it is usually convenient to pick some characteristic lengthscale of your problem and set that length to 1. See also Units in Meep.

material-type

This class is used to specify the materials that geometric objects are made of. Currently, there are three subclasses, dielectric, perfect-metal, and material-function.

-

medium - An electromagnetic medium (possibly nonlinear and/or dispersive); see also Materials in Meep. For backwards compatibility, a synonym for

mediumisdielectric. It has several properties:-

epsilon[number] - The (frequency-independent) isotropic relative permittivity, or dielectric constant. Default value = 1. You can also use

(index n)as a synonym for(epsilon (* n n)); note that this is not really the refractive index if you also specify μ, since the true index is .

.

- Using

(epsilon ε)is actually a synonym for(epsilon-diag ε ε ε). -

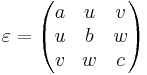

epsilon-diagandepsilon-offdiag[vector3] - These properties allow you to specify ε as an arbitrary real-symmetric tensor, by giving the diagonal and offdiagonal parts. Specifying

(epsilon-diag a b c)and/or(epsilon-offdiag u v w)corresponds to a relative permittivity tensor

- The default is the identity matrix (a = b = c = 1 and u = v = w = 0).

-

mu[number] - The (frequency-independent) isotropic relative permeability μ. Default value = 1. Using

(mu μ)is actually a synonym for(mu-diag μ μ μ). -

mu-diagandmu-offdiag[vector3] - These properties allow you to specify μ as an arbitrary real-symmetric tensor, by giving the diagonal and offdiagonal parts exactly as for ε above, again defaulting to the identity matrix.

-

D-conductivity[number] - The (frequency-independent) electric conductivity σD. Default value = 0. You can also specify an diagonal anisotropic conductivity tensor by using the property

D-conductivity-diag[vector3], which takes three numbers or a vector3 to give the σD tensor diagonal. See also Conductivity in Meep. -

B-conductivity[number] - The (frequency-independent) magnetic conductivity σB. Default value = 0. You can also specify an diagonal anisotropic conductivity tensor by using the property

B-conductivity-diag[vector3], which takes three numbers or a vector3 to give the σB tensor diagonal. See also Conductivity in Meep. -

chi2[number] - The nonlinear (Pockels) susceptibility χ(2). Default value = 0. See also Nonlinearity in Meep.

-

chi3[number] - The nonlinear (Kerr) susceptibility χ(3). Default value = 0. (See e.g. Meep Tutorial/Third harmonic generation.) See also Nonlinearity in Meep.

-

E-polarizations[list ofpolarizabilityclass] - List of dispersive polarizabilities (see below) added to the dielectric constant ε, in order to model material dispersion; defaults to none. (See e.g. Meep Tutorial/Material dispersion.) See also Material dispersion in Meep. For backwards compatibility, a synonym of

E-polarizationsispolarizations. -

H-polarizations[list ofpolarizabilityclass] - List of dispersive polarizabilities (see below) added to the permeability μ, in order to model material dispersion; defaults to none. (See e.g. Meep Tutorial/Material dispersion.) See also Material dispersion in Meep.

-

-

perfect-metal - A perfectly conducting metal; this class has no properties and you normally just use the predefined

metalobject, above. (To model imperfect conductors, use a dispersive dielectric material.) See also the predefined variablesmetal,perfect-electric-conductor, andperfect-magnetic-conductorabove. -

material-function - This material type allows you to specify the material as an arbitrary function of position. It has one property:

-

material-func[function] - A function of one argument, the position

vector3, that returns the material at that point. Note that the function you supply can return any material; wild and crazy users could even return anothermaterial-functionobject (which would then have its function invoked in turn).- Instead of

material-func, you can useepsilon-func: forepsilon-func, you give it a function of position that returns the dielectric constant at that point.

- Instead of

- Important: If your material function returns nonlinear, dispersive (Lorentzian or conducting), or magnetic materials, you should also include a list of these materials in the

extra-materialsinput variable (above) to let Meep know that it needs to support these material types in your simulation. (For dispersive materials, you need to include a material with the same γn and ωn values, so you can only have a finite number of these, whereas σn can vary continuously if you want and a matching σn need not be specified inextra-materials. For nonlinear or conductivity materials, yourextra-materialslist need not match the actual values of σ or χ returned by your material function, which can vary continuously if you want.)

-

Complex ε and μ: you cannot specify a frequency-independent complex ε or μ in Meep (where the imaginary part is a frequency-independent loss), but there is an alternative. That is because there are only two important physical situations. First, if you only care about the loss in a narrow bandwidth around some frequency, you can set the loss at that frequency via the conductivity (see Conductivity in Meep). Second, if you care about a broad bandwidth, then all physical materials have a frequency-dependent imaginary (and real) ε (and/or μ), and you need to specify that frequency dependence by fitting to Lorentzian resonances via the polarizability below.

Dispersive dielectric materials, above, are specified via a list of objects of type polarizability, which is another class with four properties:

-

polarizability - Specifies a single dispersive polarizability of damped harmonic form (see Material dispersion in Meep), with the parameters:

-

omega[number] - The resonance frequency fn = ωn / 2π.

-

gamma[number] - The resonance loss rate γn / 2π.

-

sigma[number] - The scale factor σn. You can also specify an diagonal anisotropic σ tensor by using the property

sigma-diag[vector3], which takes three numbers or a vector3 to give the σn tensor diagonal. See also Material dispersion in Meep.

-

geometric-object

This class, and its descendants, are used to specify the solid geometric objects that form the dielectric structure being simulated. The base class is:

-

geometric-object - Properties:

-

material[material-typeclass] - The material that the object is made of (usually some sort of dielectric). No default value (must be specified).

-

center[vector3] - Center point of the object. No default value.

-

One normally does not create objects of type geometric-object directly, however; instead, you use one of the following subclasses. Recall that subclasses inherit the properties of their superclass, so these subclasses automatically have the material and center properties (which must be specified, since they have no default values).

In a two-dimensional calculation, only the intersections of the objects with the x-y plane are considered.

-

sphere - A sphere. Properties:

-

radius[number] - Radius of the sphere. No default value.

-

-

cylinder - A cylinder, with circular cross-section and finite height. Properties:

-

radius[number] - Radius of the cylinder's cross-section. No default value.

-

height[number] - Length of the cylinder along its axis. No default value.

-

axis[vector3] - Direction of the cylinder's axis; the length of this vector is ignored. Defaults to point parallel to the z axis.

-

-

cone - A cone, or possibly a truncated cone. This is actually a subclass of

cylinder, and inherits all of the same properties, with one additional property. The radius of the base of the cone is given by theradiusproperty inherited fromcylinder, while the radius of the tip is given by the new property,radius2. (Thecenterof a cone is halfway between the two circular ends.)-

radius2[number] - Radius of the tip of the cone (i.e. the end of the cone pointed to by the

axisvector). Defaults to zero (a "sharp" cone).

-

-

block - A parallelepiped (i.e., a brick, possibly with non-orthogonal axes). Properties:

-

size[vector3] - The lengths of the block edges along each of its three axes. Not really a 3-vector, but it has three components, each of which should be nonzero. No default value.

-

e1,e2,e3[vector3] - The directions of the axes of the block; the lengths of these vectors are ignored. Must be linearly independent. They default to the three lattice directions.

-

-

ellipsoid - An ellipsoid. This is actually a subclass of

block, and inherits all the same properties, but defines an ellipsoid inscribed inside the block.

Here are some examples of geometric objects created using the above classes, assuming mat is some material we have defined:

; A cylinder of infinite radius and height 0.25 pointing along the x axis,

; centered at the origin:

(make cylinder (center 0 0 0) (material mat)

(radius infinity) (height 0.25) (axis 1 0 0))

; An ellipsoid with its long axis pointing along (1,1,1), centered on

; the origin (the other two axes are orthogonal and have equal

; semi-axis lengths):

(make ellipsoid (center 0 0 0) (material mat)

(size 0.8 0.2 0.2)

(e1 1 1 1)

(e2 0 1 -1)

(e3 -2 1 1))

; A unit cube of material m with a spherical air hole of radius 0.2 at

; its center, the whole thing centered at (1,2,3):

(set! geometry (list

(make block (center 1 2 3) (material mat) (size 1 1 1))

(make sphere (center 1 2 3) (material air) (radius 0.2))))

symmetry

This class is used for the symmetries input variable, to specify symmetries (which must preserve both the structure and the sources) for Meep to exploit. Any number of symmetries can be exploited simultaneously, but there is no point in specifying redundant symmetries: the computational cell can be reduced by at most a factor of 4 in 2d and 8 in 3d. See also Exploiting symmetry in Meep.

-

symmetry - A single symmetry to exploit. This is the base class of the specific symmetries below, so normally you don't create it directly. However, it has two properties which are shared by all symmetries:

-

direction[directionconstant] - The direction of the symmetry (the normal to a mirror plane or the axis for a rotational symmetry). e.g.

X,Y, ... (only Cartesian/grid directions are allowed). No default value. -

phase[cnumber] - An additional phase to multiply the fields by when operating the symmetry on them; defaults to

1.0. e.g. a phase of-1for a mirror plane corresponds to an odd mirror. (Technically, you are essentially specifying the representation of the symmetry group that your fields and sources transform under.)

-

The specific symmetry sub-classes are:

-

mirror-sym - A mirror symmetry plane. Here, the

directionis the direction normal to the mirror plane. -

rotate2-sym - A 180° (twofold) rotational symmetry (a.k.a. C2). Here, the

directionis the axis of the rotation. -

rotate4-sym - A 90° (fourfold) rotational symmetry (a.k.a. C4). Here, the

directionis the axis of the rotation.

pml

This class is used for specifying the PML absorbing boundary layers around the cell, if any, via the pml-layers input variable. See also Perfectly matched layers. pml-layers can be zero or more pml objects, with multiple objects allowing you to specify different PML layers on different boundaries.

-

pml - A single PML layer specification, which sets up one or more PML layers around the boundaries according to the following four properties.

-

thickness[number] - The spatial thickness of the PML layer (which extends from the boundary towards the inside of the computational cell). The thinner it is, the more numerical reflections become a problem. No default value.

-

direction[directionconstant] - Specify the direction of the boundaries to put the PML layers next to. e.g. if

X, then specifies PML on the boundaries (depending on the value of

boundaries (depending on the value of side, below). Default is the special valueALL, which puts PML layers on the boundaries in all directions. -

side[boundary-sideconstant] - Specify which side,

LoworHighof the boundary or boundaries to put PML on. e.g. if side isLowand direction isX, then a PML layer is added to the − x boundary. Default is the special valueALL, which puts PML layers on both sides. -

strength[number] - A strength (default is

1.0) to multiply the PML absorption coefficient by. A strength of2.0will square the theoretical asymptotic reflection coefficient of the PML (making it smaller), but will also increase numerical reflections. Alternatively, you can changeR-asymptotic, below. -

R-asymptotic[number] - The asymptotic reflection in the limit of infinite resolution or infinite PML thickness, for refections from air (an upper bound for other media with index > 1). (For a finite resolution or thickness, the reflection will be much larger, due to the discretization of Maxwell's equation.) The default value is 10−15, which should be suffice for most purposes. (You want to set this to be small enough so that waves propagating within the PML are attenuated sufficiently, but making

R-asymptotictoo small will increase the numerical reflection due to discretization.) -

pml-profile[function] - By default, Meep turns on the PML conductivity quadratically within the PML layer—one doesn't want to turn it on suddenly, because that exacerbates reflections due to the discretization. More generally, with

pml-profileone can specify an arbitrary PML "profile" function f(u) that determines the shape of the PML absorption profile up to an overall constant factor. u goes from 0 to 1 at the start and end of the PML, and the default is f(u)=u2. In some cases where a very thick PML is required, such as in a periodic medium (where there is technically no such thing as a true PML, only a pseudo-PML), it can be advantageous to turn on the PML absorption more smoothly (see Oskooi et al., 2008). For example, one can use a cubic profile f(u)=u3 by specifying(pml-profile (lambda (u) (* u u u))).

-

source

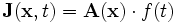

The source class is used to specify the current sources (via the sources input variable). Note that all sources in Meep are separable in time and space, i.e. of the form  for some functions

for some functions  and f. (Non-separable sources can be simulated, however, by modifying the sources after each time step.) When real fields are being used (which is the default in many cases...see the

and f. (Non-separable sources can be simulated, however, by modifying the sources after each time step.) When real fields are being used (which is the default in many cases...see the force-complex-fields? input variable), only the real part of the current source is used by Meep.

Important note: These are current sources (J terms in Maxwell's equations), even though they are labelled by electric/magnetic field components. They do not specify a particular electric/magnetic field (which would be what is called a "hard" source in the FDTD literature). There is no fixed relationship between the current source and the resulting field amplitudes; it depends on the surrounding geometry, as described in the Meep FAQ.

-

source - The source class has the following properties:

-

src[src-timeclass] - Specify the time-dependence of the source (see below). No default.

-

component[componentconstant] - Specify the direction and type of the current component: e.g.

Ex,Ey, etcetera for an electric-charge current, andHx,Hy, etcetera for a magnetic-charge current. Note that currents pointing in an arbitrary direction are specified simply as multiple current sources with the appropriate amplitudes for each component. No default. center[vector3]- The location of the center of the current source in the computational cell; no default.

size[vector3]- The size of the current distribution along each direction of the computational cell. The default is (0,0,0): a point-dipole source.

amplitude[cnumber]- An overall (complex) amplitude multiplying the the current source. Default is

1.0. amp-func[function]- A Scheme function of a single argument, that takes a vector3 giving a position and returns a (complex) current amplitude for that point. The position argument is relative to the

centerof the current source, so that you can move your current around without changing your function. The default is'()(null), meaning that a constant amplitude of 1.0 is used. Note that your amplitude function (if any) is multiplied by theamplitudeproperty, so both properties can be used simultaneously.

-

The src-time object, which specifies the time dependence of the source, can be one of the following three classes.

-

continuous-src - A continuous-wave source proportional to exp( − iωt), possibly with a smooth (exponential/tanh) turn-on/turn-off. It has the properties:

frequency[number]- The frequency f in units of c/distance (or ω in units of 2πc/distance) (see Units in Meep). No default value. You can instead specify

(wavelength x)or(period x), which are both a synonym for(frequency (/ 1 x)); i.e. 1/ω in these units is the vacuum wavelength or the temporal period. start-time[number]- The starting time for the source; default is

0(turn on at t = 0). end-time[number]- The end time for the source; default is

infinity(never turn off). width[number]- Roughly, the temporal width of the smoothing (technically, the inverse of the exponential rate at which the current turns off and on). Default is

0(no smoothing). You can instead specify(fwidth x), which is a synonym for(width (/ 1 x))(i.e. the frequency width is proportional to the inverse of the temporal width). cutoff[number]- How many

widths the current decays for before we cut it off and set it to zero; the default is3.0. A larger value ofcutoffwill reduce the amount of high-frequency components that are introduced by the start/stop of the source, but will of course lead to longer simulation times.

-

gaussian-src - A Gaussian-pulse source roughly proportional to exp( − iωt − (t − t0)2 / 2w2), It has the properties:

frequency[number]- The center frequency f in units of c/distance (or ω in units of 2πc/distance) (see Units in Meep). No default value. You can instead specify

(wavelength x)or(period x), which are both a synonym for(frequency (/ 1 x)); i.e. 1/ω in these units is the vacuum wavelength or the temporal period. width[number]- The width w used in the Gaussian. No default value. You can instead specify

(fwidth x), which is a synonym for(width (/ 1 x))(i.e. the frequency width is proportional to the inverse of the temporal width). start-time[number]- The starting time for the source; default is

0(turn on at t = 0). cutoff[number]- How many

widths the current decays for before we cut it off and set it to zero—this applies for both turn-on and turn-off of the pulse. The default is5.0. A larger value ofcutoffwill reduce the amount of high-frequency components that are introduced by the start/stop of the source, but will of course lead to longer simulation times.

-

custom-src - A user-specified source function f(t). You can also specify start/end times (at which point your current is set to zero whether or not your function is actually zero). These are optional, but you must specify an

end-timeexplicitly if you want functions likerun-sourcesto work, since they need to know when your source turns off.-

src-func[function] - The function f(t) specifying the time-dependence of the source. It should take one argument (the time in Meep units) and return a complex number.

start-time[number]- The starting time for the source; default is

(- infinity)(turn on at ). Note, however, that the simulation normally starts at t = 0 with zero fields as the initial condition, so there is implicitly a sharp turn-on at t = 0 whether you specify it or not.

). Note, however, that the simulation normally starts at t = 0 with zero fields as the initial condition, so there is implicitly a sharp turn-on at t = 0 whether you specify it or not.

end-time[number]- The end time for the source; default is

infinity(never turn off).

-

flux-region

A flux-region object is used with add-flux below to specify a region in which Meep should accumulate the appropriate Fourier-transformed fields in order to compute a flux spectrum.

flux-region- A region (volume, plane, line, or point) in which to compute the integral of the Poynting vector of the Fourier-transformed fields. Its properties are:

center[vector3]- The center of the flux region (no default).

size[vector3]- The size of the flux region along each of the coordinate axes; default is (0,0,0) (a single point).

direction[directionconstant]- The direction in which to compute the flux (e.g.

X,Y, etcetera). The default isAUTOMATIC, in which the direction is determined by taking the normal direction if the flux region is a plane (or a line, in 2d). If the normal direction is ambiguous (e.g. for a point or volume), then you must specify thedirectionexplicitly (not doing so will lead to an error). weight[cnumber]- A weight factor to multiply the flux by when it is computed; default is

1.0.

Note that the flux is always computed in the positive coordinate direction, although this can effectively be flipped by using a weight of -1.0. (This is useful, for example, if you want to compute the outward flux through a box, so that the sides of the box add instead of subtract!)

Miscellaneous functions

Here, we describe a number of miscellaneous useful functions provided by Meep.

See also the reference section of the libctl manual, which describes a number of useful functions defined by libctl.

Geometry utilities

Some utility functions are provided to help you manipulate geometric objects:

-

(shift-geometric-object obj shift-vector) - Translate

objby the 3-vectorshift-vector. -

(geometric-object-duplicates shift-vector min-multiple max-multiple obj) - Return a list of duplicates of

obj, shifted by various multiples ofshift-vector(frommin-multipletomax-multiple, inclusive, in steps of 1). -

(geometric-objects-duplicates shift-vector min-multiple max-multiple obj-list) - Same as

geometric-object-duplicates, except operates on a list of objects,obj-list. If A appears before B in the input list, then all the duplicates of A appear before all the duplicates of B in the output list. -

(geometric-objects-lattice-duplicates obj-list [ ux uy uz ]) - Duplicates the objects in

obj-listby multiples of the Cartesian basis vectors, making all possible shifts of the "primitive cell" (see below) that fit inside the lattice cell. (This is useful for supercell calculations; see the [user-tutorial.html tutorial].) The primitive cell to duplicate isuxbyuybyuz, in units of the Cartesian basis vectors. These three parameters are optional; any that you do not specify are assumed to be1. -

(point-in-object? point obj) - Returns whether or not the given 3-vector

pointis inside the geometric objectobj. -

(point-in-periodic-object? point obj) - As

point-in-object?, but also checks translations of the given object by the lattice vectors. -

(display-geometric-object-info indent-by obj) - Outputs some information about the given

obj, indented byindent-byspaces.

Output file names

The output file names used by Meep, e.g. for HDF5 files, are automatically prefixed by the input variable filename-prefix. If filename-prefix is "" (the default), however, then Meep constructs a default prefix based on the current ctl file name with ".ctl" replaced by "-": e.g. tst.ctl implies a prefix of "tst-". You can get this prefix by running:

(get-filename-prefix)- Return the current prefix string that is prepended, by default, to all file names.

If you don't want to use any prefix, then you should set filename-prefix to false.

In addition to the filename prefix, you can also specify that all the output files be written into a newly-created directory (if it does not yet exist). This is done by running:

(use-output-directory [dirname])- Put output in a subdirectory, which is created if necessary. If the optional argument dirname is specified, that that is the name of the directory. Otherwise, the directory name is the current ctl file name with

".ctl"replaced by"-out": e.g.tst.ctlimplies a directory of"tst-out".

Misc.

(volume (center ...) (size ...))- Many Meep functions require you to specify a volume in space, corresponding to the C++ type

meep::geometric_volume. This function creates such a volume object, given thecenterandsizeproperties (just like e.g. ablockobject). If thesizeis not specified, it defaults to (0,0,0), i.e. a single point. (meep-time)- Return the current simulation time (in simulation time units, not wall-clock time!). (e.g. during a run function.)

- Occasionally, e.g. for termination conditions of the form time < T?, it is desirable to round the time to single precision in order to avoid small differences in roundoff error from making your results different by one timestep from machine to machine (a difference much bigger than roundoff error); in this case you can call

(meep-round-time)instead, which returns the time rounded to single precision.

Field computations

Meep supports a large number of functions to perform computations on the fields. Currently, most of them are accessed via the lower-level C++/SWIG interface, but we are slowly adding simpler, higher-level versions of them here.

(get-field-point c pt)- Given a

componentorderived-componentconstantcand avector3pt, returns the value of that component at that point. (get-epsilon-point pt)- Equivalent to

(get-field-point Dielectric pt). (flux-in-box dir box)- Given a

directionconstant, and ameep::volume*, returns the flux (the integral of![\Re [\mathbf{E}^* \times \mathbf{H}]](/wiki/images/math/d/f/5/df5da403fca9de978b2fa3e687a18286.png) ) in that volume. Most commonly, you specify a volume that is a plane or a line, and a direction perpendicular to it, e.g.

) in that volume. Most commonly, you specify a volume that is a plane or a line, and a direction perpendicular to it, e.g. (flux-in-box X (volume (center 0) (size 0 1 1))). (electric-energy-in-box box)- Given a

meep::volume*, returns the integral of the electric-field energy in the given volume. (If the volume has zero size along a dimension, a lower-dimensional integral is used.)

in the given volume. (If the volume has zero size along a dimension, a lower-dimensional integral is used.)

(magnetic-energy-in-box box)- Given a

meep::volume*, returns the integral of the magnetic-field energy in the given volume. (If the volume has zero size along a dimension, a lower-dimensional integral is used.)

in the given volume. (If the volume has zero size along a dimension, a lower-dimensional integral is used.)

(field-energy-in-box box)- Given a

meep::volume*, returns the integral of the electric+magnetic-field energy in the given volume. (If the volume has zero size along a dimension, a lower-dimensional integral is used.)

in the given volume. (If the volume has zero size along a dimension, a lower-dimensional integral is used.)

Note that if you are at a fixed frequency and you use complex fields (Bloch-periodic boundary conditions or fields-complex?=true), then one half of the flux or energy integrals above corresponds to the time-average of the flux or energy for a simulation with real fields.

Often, you want the integration box to be the entire computational cell. A useful function to return this box, which you can then use for the box arguments above, is (meep-fields-total-volume fields), where fields is the global variable (above) holding the current meep::fields object.

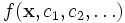

One powerful feature is that you can supply an arbitrary function  of position

of position  and various field components

and various field components  and ask Meep to integrate it over a given volume, find its maximum, or output it (via

and ask Meep to integrate it over a given volume, find its maximum, or output it (via output-field-function, described later). This is done via the functions:

(integrate-field-function cs func [where] [fields-var])- Returns the integral of the complex-valued function

funcover themeep::geometric_volumespecified bywhere(defaults to entire computational cell) for themeep::fieldsspecified byfields-var(defaults tofields).funcis a function of position (avector3, its first argument) and zero or more field components specified bycs: a list ofcomponentconstants.funccan be real- or complex-valued. - (If any dimension of

whereis zero, that dimension is not integrated over. In this way you can specify one-, two-, or three-dimensional integrals.) (max-abs-field-function cs func [where] [fields-var])- As

integrate-field-function, but returns the maximum absolute value offuncin the volumewhereinstead of its integral.

(The integration is performed by summing over the grid points with a simple trapezoidal rule, and the maximum is similarly over the grid points.) See also Meep field-function examples for illustrations of how to call integrate-field-function and max-abs-field-function. See also Synchronizing the magnetic and electric fields if you want to do computations combining the electric and magnetic fields.

Occasionally, one wants to compute an integral that combines fields from two separate simulations (e.g. for nonlinear coupled-mode calculations). This functionality is supported in Meep, as long as the two simulations have the same computational cell, the same resolution, the same boundary conditions and symmetries (if any), and the same PML layers (if any).

(integrate2-field-function fields2 cs1 cs2 func [where] [fields-var])- Similar to

integrate-field-function, but takes additional parametersfields2andcs2.fields2is ameep::fields*object similar to the globalfieldsvariable (see below) specifying the fields from another simulation.cs1is a list of components to integrate with fromfields-var(defaults tofields), as forintegrate-field-function, whilecs2is a list of components to integrate fromfields2. Similar tointegrate-field-function,funcis a function that returns an number given arguments consisting of: the position vector, followed by the values of the components specified bycs1(in order), followed by the values of the components specified bycs2(in order).

To get two fields in memory at once for integrate2-field-function, the easiest way is to run one simulation within a given .ctl file, then save the results in another fields variable, then run a second simulation. This would look something like:

...set up and run first simulation... (define fields2 fields) ; save the fields in a variable (set! fields '()) ; prevent the fields from getting deallocated by reset-meep (reset-meep) ...set up and run second simulation...

It is also possible to timestep both fields simultaneously (e.g. doing one timestep of one simulation then one timestep of another simulation, and so on, but this requires you to call much lower-level functions like (meep-fields-step fields).

Reloading parameters

Once the fields/simulation have been initialized, you can change the values of various parameters by using the following functions:

(reset-meep)- Reset all of Meep's parameters, deleting the fields, structures, etcetera, from memory as if you had not run any computations.

(restart-fields)- Restart the fields at time zero, with zero fields. (Does not reset the Fourier transforms of the flux planes, which continue to be accumulated.)

(change-k-point! k)- Change the

k-point(the Bloch periodicity). (change-sources! new-sources)- Change the

sourcesinput variable tonew-sources, and changes the sources used for the current simulation.

(More to come...)

Flux spectra

Given a bunch of flux-region objects (see above), you can tell Meep to accumulate the Fourier transforms of the fields in those regions in order to compute flux spectra. See also the transmission/reflection spectra introduction and the Meep tutorial. The most important function is:

(add-flux fcen df nfreq flux-regions...)- Add a bunch of

flux-regions to the current simulation (initializing the fields if they have not yet been initialized), telling Meep to accumulate the appropriate field Fourier transforms fornfreqequally spaced frequencies covering the frequency rangefcen-df/2tofcen+df/2. Return a flux object, which you can pass to the functions below to get the flux spectrum, etcetera.

As described in the tutorial, you normally use add-flux via statements like:

(define transmission (add-flux ...))

to store the flux object in a variable. add-flux initializes the fields if necessary, just like calling run, so you should only call it after setting up your geometry, sources, pml-layers, etcetera. You can create as many flux objects as you want, e.g. to look at powers flowing in different regions or in different frequency ranges. Note, however, that Meep has to store (and update at every time step) a number of Fourier components equal to the number of grid points intersecting the flux region multiplied by the number of electric and magnetic field components required to get the Poynting vector multiplied by nfreq, so this can get quite expensive (in both memory and time) if you want a lot of frequency points over large regions of space.

Once you have called add-flux, the Fourier transforms of the fields are accumulated automatically during time-stepping by the run functions. At any time, you can ask for Meep to print out the current flux spectrum via:

(display-fluxes fluxes...)- Given a number of flux objects, this displays a comma-separated table of frequencies and flux spectra, prefixed by "flux1:" or similar (where the number is incremented after each run). All of the fluxes should be for the same

fcen/df/nfreq. The first column are the frequencies, and subsequent columns are the flux spectra.

You might have to do something lower-level if you have multiple flux regions corresponding to different frequency ranges, or have other special needs. (display-fluxes f1 f2 f3) is actually equivalent to (display-csv "flux" (get-flux-freqs f1) (get-fluxes f1) (get-fluxes f2) (get-fluxes f3), where display-csv takes a bunch of lists of numbers and prints them as a comma-separated table, and we are calling two lower-level functions:

(get-flux-freqs flux)- Given a flux object, returns a list of the frequencies that it is computing the spectrum for.

(get-fluxes flux)- Given a flux object, returns a list of the current flux spectrum that it has accumulated.

As described in the Meep tutorial, for a reflection spectrum you often want to save the Fourier-transformed fields from a "normalization" run and then load them into another run to be subtracted. This can be done via:

(save-flux filename flux)- Save the Fourier-transformed fields corresponding to the given flux object in an HDF5 file of the given name (without the ".h5" suffix) (the current filename-prefix is prepended automatically).

(load-flux filename flux)- Load the Fourier-transformed fields into the given flux object (replacing any values currently there) from an HDF5 file of the given name (without the ".h5" suffix) (the current filename-prefix is prepended automatically). You must load from a file that was saved by

save-fluxin a simulation of the same dimensions (for both the computational cell and the flux regions) with the same number of processors. (load-minus-flux filename flux)- As

load-flux, but negates the Fourier-transformed fields after they are loaded. This means that they will be subtracted from any future field Fourier transforms that are accumulated. (scale-flux-fields s flux)- Scale the Fourier-transformed fields in

fluxby the complex numbers. e.g.load-minus-fluxis equivalent toload-fluxfollowed byscale-flux-fieldswiths=-1.

Frequency-domain solver

Meep contains a frequency-domain solver that directly computes the fields produced in a geometry in response to a constant-frequency source, using an iterative linear solver instead of timestepping. Preliminary tests have shown that in many instances, this solver converges much faster than simply running an equivalent time domain simulation with a continuous wave source, timestepping until all transient effects from the source turn-on have disappeared. To use it, simply define a continuous-src with the desired frequency, initialize the fields and geometry via (init-fields), and then:

(meep-fields-solve-cw fields tol maxiters L)

The parameters to the frequency-domaine solver are tol the tolerance (10−8, by default), a maximum number of iterations maxiters (10−4, by default). Finally, there is a parameter L that determines a tradeoff between memory and work per step and convergence rate of the iterative algorithm biCGSTAB-(L) that is used; larger values of L of will often lead to faster convergence at the expense of more memory and more work per iteration. The default is L=2, and normally a value ≥ 2 should be used.

The frequency-domain solver supports arbitrary geometries, PML, boundary conditions, symmetries, parallelism, conductors, and arbitrary nondispersive materials. Lorentz–Drude dispersive materials are not currently supported in the frequency-domain solver, but since you are solving at a known fixed frequency rather than timestepping, you should be able to pick conductivities etcetera in order to obtain any desired complex ε and μ at that frequency.

Run and step functions

The actual work in Meep is performed by run functions, which time-step the simulation for a given amount of time or until a given condition is satisfied.

The run functions, in turn, can be modified by use of step functions: these are called at every time step and can perform any arbitrary computation on the fields, do outputs and I/O, or even modify the simulation. The step functions can be transformed by many modifier functions, like at-beginning, during-sources, etcetera which cause them to only be called at certain times, etcetera, instead of at every time step.

A common point of confusion is described in the article: The run function is not a loop. Please read this article if you want to make Meep do some customized action on each time step, as many users make the same mistake. What you really want to in that case is to write a step function, as described below.

Run functions

The following run functions are available. (You can also write your own, using the lower-level C++/SWIG functions, but these should suffice for most needs.)

(run-until cond?/time step-functions...)- Run the simulation until a certain time or condition, calling the given step functions (if any) at each timestep. The first argument is either a number, in which case it is an additional time (in Meep units) to run for, or it is a function (of no arguments) which returns

truewhen the simulation should stop. (run-sources step-functions...)- Run the simulation until all sources have turned off, calling the given step functions (if any) at each timestep. Note that this does not mean that the fields will be zero at the end: in general, some fields will still be bouncing around that were excited by the sources.

(run-sources+ cond?/time step-functions...)- As

run-sources, but with an additional first argument: either a number, in which case it is an additional time (in Meep units) to run for after the sources are off, or it is a function (of no arguments). In the latter case, the simulation runs until the sources are off and(cond?)returnstrue.

In particular, a useful first argument to run-sources+ or run-until is often given by (as in the Meep tutorial):

(stop-when-fields-decayed dT c pt decay-by)- Return a

cond?function, suitable for passing torun-until/run-sources+, that examines the componentc(e.g.Ex, etc.) at the pointpt(avector3) and keeps running until its absolute value squared has decayed by at leastdecay-byfrom its maximum previous value. In particular, it keeps incrementing the run time bydT(in Meep units) and checks the maximum value over that time period—in this way, it won't be fooled just because the field happens to go through 0 at some instant. - Note that, if you make

decay-byvery small, you may need to increase thecutoffproperty of your source(s), to decrease the amplitude of the small high-frequency components that are excited when the source turns off. (High frequencies near the Nyquist frequency of the grid have slow group velocities and are absorbed poorly by PML.)

Finally, another two run functions, useful for computing ω(k) band diagrams, are

(run-k-point T k)- Given a

vector3k, runs a simulation for each k point (i.e. specifying Bloch-periodic boundary conditions) and extracts the eigen-frequencies, and returns a list of the (complex) frequencies. In particular, you should have specified one or more Gaussian sources. It will run the simulation until the sources are turned off plus an additionalTtime units. It will runharminv(see below) at the same point/component as the first Gaussian source and look for modes in the union of the frequency ranges for all sources. (run-k-points T k-points)- Given a list

k-pointsof k vectors, runsrun-k-pointfor each one, and returns a list of lists of frequencies (one list of frequencies for each k). Also prints out a comma-delimited list of frequencies, prefixed byfreqs:, and their imaginary parts, prefixed byfreqs-im:. (See e.g. this band diagram tutorial.)

Predefined step functions

Several useful step functions are predefined for you by Meep.

Output functions

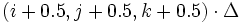

The most common step function is an output function, which outputs some field component to an HDF5 file. Normally, you will want to modify this by one of the at- functions, below, as outputting a field at every time step can get quite time- and storage-consuming.

Note that although the various field components are stored at different places in the Yee lattice, when they are outputted they are all linearly interpolated to the same grid: to the points at the centers of the Yee cells, i.e.  in 3d.

in 3d.

The predefined output functions are:

output-epsilon- Output the dielectric function (relative permittivity) ε. Note that this only outputs the frequency-independent part of ε (the

limit).

limit).

output-mu- Output the relative permeability function μ. Note that this only outputs the frequency-independent part of μ (the

limit).

limit).

output-hpwr- Output the magnetic-field energy density

output-dpwr- Output the electric-field energy density

output-tot-pwr- Output the total electric and magnetic energy density. Note that you might want to wrap this step function in

synchronized-magneticto compute it more accurately; see Synchronizing the magnetic and electric fields. output-Xfield-x,output-Xfield-y,output-Xfield-z,output-Xfield-r,output-Xfield-p- Output the x, y, z, r, or φ component respectively, of the field X, where X is either

h,b,e,d, orsfor the magnetic, electric, displacement, or Poynting field, respectively. If the field is complex, outputs two datasets, e.g.ex.randex.i, within the same HDF5 file for the real and imaginary parts, respectively. Note that for outputting the Poynting field, you might want to wrap the step function insynchronized-magneticto compute it more accurately; see Synchronizing the magnetic and electric fields. output-Xfield- Outputs all the components of the field X, where X is either

h,b,e,d, orsas above, to an HDF5 file. (That is, the different components are stored as different datasets within the same file.) (output-png component h5topng-options)- Output the given field component (e.g.

Ex, etc.) as a PNG image, by first outputting the HDF5 file, then converting to PNG via h5topng, then deleting the HDF5 file. The second argument is a string giving options to pass to h5topng (e.g."-Zc bluered"). See also the Meep tutorial. - It is often useful to use the

h5topng -Cor-Aoptions to overlay the dielectric function when outputting fields. To do this, you need to know the name of the dielectric-function.h5file (which must have been previously output by output-epsilon). To make this easier, a built-in shell variable$EPSis provided which refers to the last-output dielectric-function.h5file. So, for example(output-png Ez "-C $EPS")will output the Ez field and overlay the dielectric contours. (output-png+h5 component h5topng-options)- Like

output-png, but also outputs the.h5file for the component. (In contrast,output-pngdeletes the.h5when it is done.)

More generally, it is possible to output an arbitrary function of position and zero or more field components, similar to the integrate-field-function described above. This is done by:

- (output-field-function name cs func)

- Output the field function

functo an HDF5 file in the datasets namedname.randname.i(for the real and imaginary parts). Similar tointegrate-field-function,funcis a function of position (avector3) and the field components corresponding tocs: a list ofcomponentconstants. - (output-real-field-function name cs func)

- As

output-field-function, but only outputs the real part offuncto the dataset given by the stringname.

See also Meep field-function examples. See also Synchronizing the magnetic and electric fields if you want to do computations combining the electric and magnetic fields.

Harminv

The following step function collects field data from a given point and runs Harminv on that data to extract the frequencies, decay rates, and other information.

(harminv c pt fcen df [maxbands])- Returns a step function that collects data from the field component

c(e.g.Ex, etc.) at the given pointpt(avector3). Then, at the end of the run, it uses Harminv to look for modes in the given frequency range (centerfcenand widthdf), printing the results to standard output (prefixed byharminv:) as comma-delimited text, and also storing them to the variableharminv-results. The optional argumentmaxbandsis the maximum number of modes to search for; defaults to100.

Important: normally, you should only use harminv to analyze data after the sources are off. Wrapping it in (after-sources (harminv ...)) is sufficient.

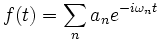

In particular, Harminv takes the time series f(t) corresponding to the given field component as a function of time and decomposes it (within the specified bandwidth) as:

The results are stored in the list harminv-results, which is a list of tuples holding the frequency, amplitude, and error of the modes. Given one of these tuples, you can extract its various components with one of the accessor functions:

(harminv-freq result)- Return the complex frequency ω (in the usual Meep 2πc units).

(harminv-freq-re result)- Return the real part of the frequency ω.

(harminv-freq-im result)- Return the imaginary part of the frequency ω.

(harminv-Q result)- Return dimensionless lifetime, or "quality factor", Q, defined as

.

.

(harminv-amp result)- Return the complex amplitude a.

(harminv-err result)- A crude measure of the error in the frequency (both real and imaginary)...if the error is much larger than the imaginary part, for example, then you can't trust the Q to be accurate. Note: this error is only the uncertainty in the signal processing, and tells you nothing about the errors from finite resolution, finite cell size, and so on!

For example, (map harminv-freq-re harminv-results) gives you a list of the real parts of the frequencies, using the Scheme built-in map.

Step-function modifiers

Rather than writing a brand-new step function every time we want to do something a bit different, the following "modifier" functions take a bunch of step functions and produce new step functions with modified behavior. (See also the Meep tutorial for examples.)

Miscellaneous step-function modifiers

(combine-step-funcs step-functions...)- Given zero or more step functions, return a new step function that (on each step) calls all of the passed step functions.

(synchronized-magnetic step-functions...)- Given zero or more step functions, return a new step function that (on each step) calls all of the passed step functions with the magnetic field synchronized in time with the electric field. See Synchronizing the magnetic and electric fields.

Controlling when a step function executes

(when-true cond? step-functions...)- Given zero or more step functions and a condition function

cond?( a function of no arguments), evaluate the step functions whenever(cond?)returnstrue. (when-false cond? step-functions...)- Given zero or more step functions and a condition function

cond?( a function of no arguments), evaluate the step functions whenever(cond?)returnsfalse. (at-every dT step-functions...)- Given zero or more step functions, evaluates them at every time interval of

dTunits (rounded up to the next time step). (after-time T step-functions...)- Given zero or more step functions, evaluates them only for times after a

Ttime units have elapsed from the start of the run. (before-time T step-functions...)- Given zero or more step functions, evaluates them only for times before a

Ttime units have elapsed from the start of the run. (at-time T step-functions...)- Given zero or more step functions, evaluates them only once, after a

Ttime units have elapsed from the start of the run. (after-sources step-functions...)- Given zero or more step functions, evaluates them only for times after all of the sources have turned off.

(after-sources+ T step-functions...)- Given zero or more step functions, evaluates them only for times after all of the sources have turned off, plus an additional

Ttime units have elapsed. (during-sources step-functions...)- Given zero or more step functions, evaluates them only for times before all of the sources have turned off.

(at-beginning step-functions...)- Given zero or more step functions, evaluates them only once, at the beginning of the run.

(at-end step-functions...)- Given zero or more step functions, evaluates them only once, at the end of the run.

Modifying HDF5 output

(in-volume v step-functions...)- Given zero or more step functions, modifies any output functions among them to only output a subset (or a superset) of the computational cell, corresponding to the

meep::geometric_volume*v(created by thevolumefunction). (in-point pt step-functions...)- Given zero or more step functions, modifies any output functions among them to only output a single point of data, at

pt(avector3). (to-appended filename step-functions...)- Given zero or more step functions, modifies any output functions among them to append their data to datasets in a single newly-created file named

filename(plus an.h5suffix and the current filename prefix). They append by adding an extra dimension to their datasets, corresponding to time. (with-prefix prefix step-functions...)- Given zero or more step functions, modifies any output functions among them to prepend the string

prefixto the file names (much likefilename-prefix, above).

Writing your own step functions

A step function can take two forms. The simplest is just a function of no arguments, which is called at every time step (unless modified by one of the modifier functions above). e.g.

(define (my-step) (print "Hello world!\n"))

If one then does (run-until 100 my-step), Meep will run for 100 time units and print "Hello world!" at every time step.

This suffices for most purposes. However, sometimes you need a step function that opens a file, or accumulates some computation, and you need to clean up (e.g. close the file or print the results) at the end of the run. For this case, you can write a step function of one argument: that argument will either be 'step when it is called during time-stepping, or 'finish when it is called at the end of the run.

Low-level functions

By default, Meep reads input functions like sources and geometry and creates global variables structure and fields to store the corresponding C++ objects. Given these, you can then call essentially any function in the C++ interface, because all of the C++ functions are automatically made accessible to Scheme by a wrapper-generator program called SWIG

Initializing the structure and fields

The structure and fields variables are automatically initialized when any of the run functions is called, or by various other functions such as add-flux. To initialize them separately, you can call (init-fields) manually, or (init-structure k-point) to just initialize the structure.

If you want to time step more than one field simultaneously, the easiest way is probably to do something like:

(init-fields) (define my-fields fields) (set! fields '()) (reset-meep)

and then change the geometry etc. and re-run (init-fields). Then you'll have two field objects in memory.

SWIG wrappers

If you look at a function in the C++ interface, then there are a few simple rules to infer the name of the corresponding Scheme function.

- First, all Meep functions (in the

meep::namespace) are prefixed withmeep-in the Scheme interface. - Second, any method of a class is prefixed with the name of the class and a hyphen. For example,

meep::fields::step, which is the function that performs a time-step, is exposed to Scheme asmeep-fields-step. Moreover, you pass the object as the first argument in the Scheme wrapper. e.g.f.step()becomes(meep-fields-step f). - To call the C++ constructor for a type, you use

new-type. e.g.(new-meep-fields ...arguments...)returns a newmeep::fieldsobject. Conversely, to call the destructor and deallocate an object, you usedelete-type; most of the time, this is not necessary because objects are automatically garbage-collected.

Some argument type conversion is performed automatically, e.g. types like complex numbers are converted to complex<double>, etcetera. vector3 vectors are converted to meep::vec, but to do this we need to know the dimensionality of the problem in C++. The problem dimensions are automatically initialized by init-structure, but if you want to pass vector arguments to C++ before that time you should call (require-dimensions!), which infers the dimensions from the geometry-lattice, k-point, and dimensions variables.